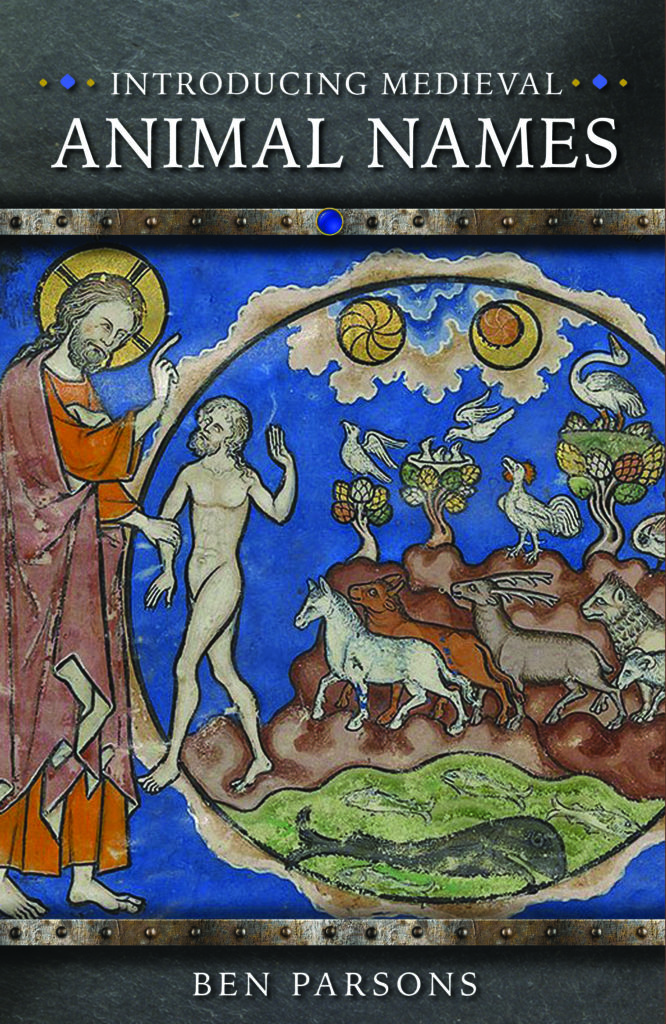

Ben Parsons introduces his book, Introducing Medieval Animal Names.

Technically we could call animals anything we wished. They would not care what incomprehensible noises we silly humans attached to them. Nor would their names be likely to embarrass them: as Mark Twain reminds us, man is the only ‘Animal that Blushes’ or ‘has occasion to’, and it was Derrida, not his cat, that cringed with shame when his pet walked in on him undressing.

Yet our names for animals tend to be highly conventionalised. The dog-names yelled over playing-fields, the horse-names that populate betting slips, the identifiers with which lab mice are tagged – all fall into distinctive patterns and styles. There are even sub-divisions of names within the same species. We would not give working or pet-dogs the elaborate multipart names kennel clubs impose on show-dogs, for instance. It is therefore hard to avoid the sense that a sort of grammar underlies the names we give to creatures, a code that reflects and reinforces our classification of the animal world.

These are the themes that I explore in Introducing Medieval Animal Names. The book examines the appellations given to pets, livestock, mounts, even wild beasts and birds in the Middle Ages, in order to expose the everyday ways in which non-human organisms were perceived and defined in the period. In some ways, medieval culture can be surprisingly coy about these terms. In part this is because they belong to the verbal rather than written order, but it also shows how naming is inseparable from valuation – the very act of recording a name signals that it and its bearer is significant in some way for a text or author.

The names that do survive represent a remarkably varied and imaginative corpus. There are affectionate names: dogs called Purboy (Pure-boy), Petitcrue (Little-cry) and Okinamaro (Silly Old Boy), cats called Martino or Bun, even cows called Amorosa (Friendly) and Mansa (Meek). There are deliberately weird names, usually given to creatures considered monstrous in some way, such as the whales Lynbakr (Heather-backed) and Jasconius (Great-fish), or Coutaut (Stump-tail), the man-eating wolf who terrorised Paris in 1439. There are even a number of joke-names: the English dog-names Dredefull, Filthe, Orribul, the German Nieman (Nobody) and Wass du (Hey you), and Doctor Joannes Cavallus (Dr John Horse), a mare François Rabelais supposedly enrolled for a medical degree in the 1530s.

However, beyond the playfulness there are serious lessons to be learned from medieval naming practices. The book as a whole not only offers a survey of these labels, but thinks about how they reveal larger attitudes to the natural world before industrialisation. After all, much as we might coo to our cats and birds, animal names are really human beings talking to themselves, and passing human judgements on non-human organisms.

Ben Parsons is Associate Professor in Late Medieval and Early Modern Literature at the University of Leicester.