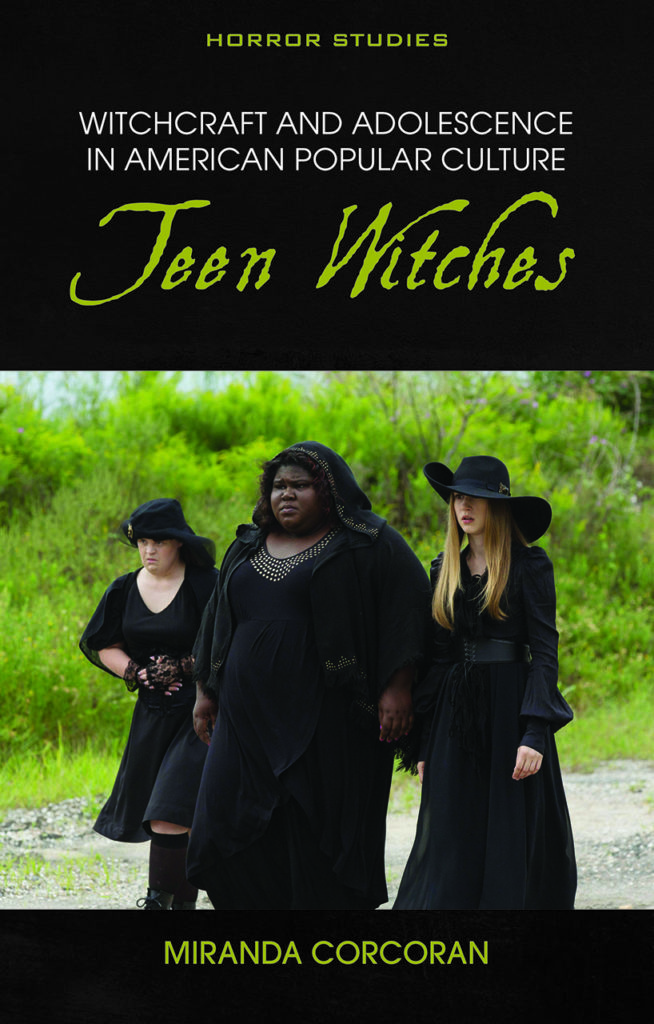

Miranda Corcoran introduces Witchcraft and Adolescence in American Popular Culture: Teen Witches.

The teenage girl is a surprisingly novel cultural archetype. Although conceptions of both adolescence and youth have a long history, the ‘teenager’ as a distinct demographic is a comparatively recent innovation. As Jon Savage points out in his thoughtful study Teenage: The Creation of Youth, the term ‘teenager’ was not widely used before 1944. Arriving alongside the massive social and cultural upheavals of the post-Second World War period, the American teenager embodied the myriad contradictions of an era defined by affluence and placidity, as well anxiety and uncertainty. Although parents, teachers and social workers were concerned about the seemingly rebellious attitudes of young men, teen girls appeared to pose a unique challenge to the American status quo. On the one hand, the teenage girl represented affluence and possibility – she was the golden, shining daughter of a newly triumphant America. On the other hand, she held immense potential for social disruption and sexual transgression.

In the popular press, the teenage girl was often framed as superficial, avaricious and precociously sexual. In a disturbing review of Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel Lolita, the critic Richard Schickel described the book’s tragic heroine, twelve-year-old Dolores Haze, as ‘that most repugnant of all females, a mid-twentieth century pubescent American girl-woman’. Similarly, in 1945, one US newsreel proclaimed ‘the emergence of the teenage girl as an American institution in her own right’ to be one of the most ‘fascinating’ yet ‘completely irrelevant’ phenomena of the period.

Teen girls were roundly condemned for the intensity of their friendships, the depth of their devotion to singers and movie stars, and the indecipherability of their slang. Yet, for all the discourse generated by the emergence of the teenage girl, her newness meant that she lacked a readily available language through which she could be discussed or understood. Writers and commentators struggled to find appropriate terms through which to represent teenage girls, and, as scholar Ilana Nash observes, they were ultimately forced to import terms from other areas of life. Nash notes that teenage girls were often discussed in ‘quasi-anthropological’ terms, couched in the kind of language mid-century anthropologists might have used to describe remote Amazonian tribes. As such, publications from the 1940s and 1950s regularly portrayed teenage girls as ‘tribal’, alluding to their strange ‘rituals’ and cult-like social organisation. At the same time, journalists writing about the new phenomenon of the teen girl often described her in animalistic terms: bright and colourful like a butterfly or bird, or else devious and spoiled like a cat.

This is where the teenage witch makes her debut. Although writers were borrowing language from an array of different fields – from biology and zoology to anthropology – in an attempt to explain the uniqueness of the adolescent female, many authors (and later filmmakers) would turn to history and/or fantasy to find an appropriate analogue for the teenage girl. The teenage girl appeared, to many contemporary commentators, to display numerous parallels with the mythic figure of the witch. Like the witch, the teen girl was restless, metamorphic, uncontainable and driven by desire. Her peer groups appeared – at least, to outsiders – to possess all the esoteric features of the witches’ coven, while her social activities seemed almost ritualistic in nature.

Witches have a long history of being put to work – in art, literature and religious or political discourse – as metaphorical or iconic conceits. Alongside a very real (and indeed tragic) history of witchcraft beliefs and persecutions, witches have embodied a range of diverse concepts. They have stood for female sexual disorder, political upheaval, and moral inversion, and they have been employed to conceptualise projects as diverse as religious reform and colonial expansion. The importation of the witch into mid-twentieth-century discussion of the emerging teenage phenomenon can therefore be seen as part of a much wider, and indeed older, practice of utilising witchcraft as a rhetorical device.

Perhaps the first American writer to employ the sorceress as a trope, or conceptual device, through which to explore adolescent femininity was Marion L. Starkey. Her 1949 book, The Devil in Massachusetts: A Modern Inquiry into the Salem Witch Trials, is an utterly fascinating text. Although numerous critics have denounced its anachronistic tendencies, particularly with regard to its treatment of youth and adolescence, it is in fact these overt anachronisms that make her work so interesting. In her book, Starkey describes the afflicted girls – the circle of young women supposedly bewitched by Salem’s diabolical hordes – as ‘bobby-soxers’. This term, which described the newly emergent teen girl obsessed with dancing, fashion and popular crooners like Frank Sinatra, is very much a mid-twentieth-century coinage. As such, Starkey’s description of the Salem girls as a ‘pack of bobby-soxers’ is decidedly anachronistic. Indeed, throughout her book, Starkey seems less interested in exploring the Salem witch trials as an historical event than in using the trials as a lens through which to explore modern ideas of adolescence. The Devil in Massachusetts thus attributes the Essex County witchcraft panic to teenage boredom, the hormonal discord of puberty and sexual frustration. Significantly, Starkey’s book would go on to become a massive influence on Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible. While The Crucible has entered literary history as a powerful allegory for the injustices carried out under the auspices of 1950s anticommunism, it also provides a fascinating insight into contemporary ideas about female adolescence. After all, the village’s descent into paranoia and accusation is, in Miller’s play, initiated by the sexual jealousy of the teenage Abigail Miller. The play also presents the girls at the heart of the trials as hormonal, petty and cliquish – all characteristics associated with teenage girls in the 1950s.

Starkey and Miller use witchcraft as a trope. Tropes are rhetorical devices which the historian Hayden White claims are employed to make the unfamiliar familiar by aligning it with pre-existing ideas and concepts. In this case, authors working in the immediate post-Second World War period made the teenage girl familiar by connecting her to the well-known figure of the witch. In subsequent decades, other authors, filmmakers and screenwriters would undertake a similar project. Just five years after Arthur Miller wrote The Crucible, Elizabeth George Speare’s YA novel The Witch of Blackbird Pond would use witchcraft as a metaphor for the experience of growing up and learning to be true to oneself. Later, in 1962, the character of Sabrina the Teenage Witch made her debut in Archie Comics, where she embodied the mischievous allure of adolescence. Over the course of the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first, teen witches have embodied the diversity of the adolescent experience. From Stephen King’s horror novel Carrie (1974) to the cheesy 1989 musical comedy Teen Witch, these texts all utilise the teen witch to reflect and conceptualise female adolescence. In recent years, teen witch texts like American Horror Story: Coven (2013) and The Witch (2015) have employed the figure of the adolescent sorceress to explore complex issues related to sexual violence, bodily autonomy, power and agency. More exciting still, in the last decade or so, works produced by queer and trans authors, and by writers of colour, have moved the witch away from her heteronormative, Eurocentric roots. Afia Atakora’s 2020 novel Conjure Women centres on a teen (and later in the book, young adult) witch steeped in Black religio-magical traditions. Similarly, Aiden Thomas’s novel Cemetery Boys (also from 2020, and which I was unfortunately unable to include in my book) focuses on a young trans boy raised in the syncretic practice of brujería. The teenage witch is an intriguing archetype with a fascinating, albeit recent, history. Since the 1940s, she has served as a trope through which shifting ideas about female adolescence could be conceptualised, explored and expanded. She has always been a dynamic, metamorphic figure, and in recent years has transformed immensely. As we move through the 2020s, we will encounter many more fictional teen witches, including an ever-increasing number of witches of colour, queer witches, trans and nonbinary witches, all of whom will speak to immense diversity and complexity of the adolescent experience.

Bibliography

Ilana Nash, American Sweethearts: Teenage Girls in Twentieth-Century Popular Culture (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 2006)

Peter Rabinowitz, ‘Lolita: Solipsized or Sodomized?; or, Against Abstraction – in General’, in Walter Jost and Wendy Olmsted (eds), A Companion to Rhetoric and Rhetorical Criticism (London: Blackwell, 2004)

Jon Savage, Teenage: The Creation of Youth, 1875–1945 (London: Chatto & Windus, 2007)

Hayden White, Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism (Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978)