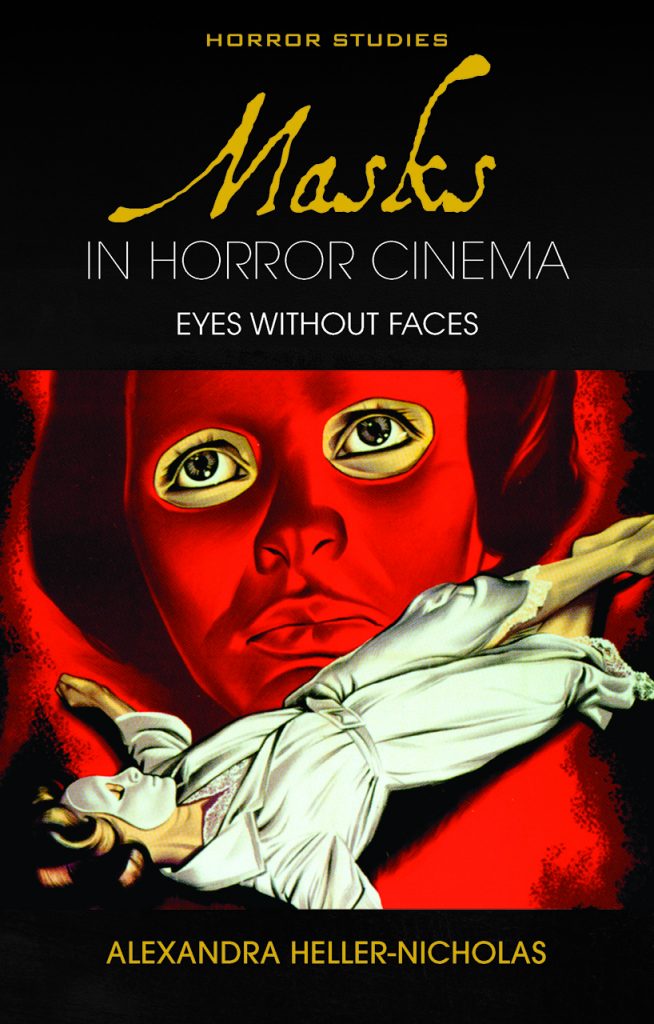

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas introduces her book Masks in Horror Cinema: Eyes Without Faces.

In 2019, the University of Wales Press published my book, Masks in Horror Cinema: Eyes Without Faces, as part of its Horror Studies series. During the many years of research and writing that led to the book’s release, one question was always at the front of my mind: how do I write a book about one of the most ubiquitous yet under-studied iconographic elements of the horror genre, but simultaneously balance it with the bigger questions around identity, politics and power that I was more broadly interested in? To keep these later elements to the forefront of my analysis as I worked through the history of masks in horror movies, I focused explicitly on a number of central concepts that effectively became the drumbeat to which my book danced: power, ritual and transformation.

These three elements lie at the heart of not just how the mask has functioned in horror but, more importantly, why and how it has endured in the genre: not only why and how it has lasted from the very early days of cinema (and, indeed, can be traced back to the genre’s origins in gothic literature), but also why and how it has crossed cultural boundaries as demonstrated by films made all around the world. Regardless of the specifics of a given film’s historical moment or other production factors, the mask has endured because its symbolic language is built into the history of civilisation itself, visible from an archaeological perspective in some of the earliest cultures that formed on our planet. Importantly, from this perspective the mask doesn’t always ‘mean’ the same thing; to reductively flatten what masks ‘do’ is an insult to the uniqueness of the individual cultures and historical moments that have spanned literally thousands and thousands of years. But at the same time, these variations manifest on a conceptual plane where, on some level, power, ritual and transformation intersect in myriad ways that speak to the very force of presence of the mask-as-object itself.

When I wrote the book, after looking at masks through the lens of material history and its evolution in cinema history from different cultures and national contexts, I identified five core categories across which masks in the genre could be conceived in the post-codification period that began in the 1970s with the rise of the slasher genre in particular. The trends that I found dominating the kinds of masks being utilised in horror were skin masks, blank masks, animal masks, repurposed masks, and technological masks. In regard to the latter especially, I examined how from an anthropological perspective masks could be considered technologies of transformation in and of themselves, analogue devices that trigger change. But I also looked at masks in terms of the deceptive identities so pervasive – and even encouraged – by social media, and also rethought how the object of the camera in the found-footage horror film could be reconceived as a mask of sorts, reworking ideas from my earlier book Found Footage Horror Films: Fear and the Appearance of Reality (2015).

But that was then, and this is now. What I did not know when Masks in Horror Cinema was released in 2019 – and what no one knew – was that another section of the book contained what would (or could) within a year of its publication be considered its most explicitly political content. My interest in masks with more neutral, non-horror related wear (welding masks, gas masks, ski masks, etc.) all fell under the umbrella of what I termed ‘repurposed’ masks: ‘objects whose initial, intended functions are redeployed in horror to create new cultural meanings’. Three of these case studies – Dead Ringers (David Cronenberg, 1988), Anatomy (Stefan Ruzowitzky, 2000), and Carved: The Slit-Mouthed Woman (Kōji Shiraishi, 2007) – involved surgical masks, an object which, at the time of writing this blog in 2020, has garnered an entirely new array of cultural, social and political meanings. Across my analysis of these three films in particular, I explored a number of features evoked by the symbolic presence of the surgical mask with a particular emphasis on their cultural specificity to their place of production (Canada, Germany and Japan respectively). But, despite these very different contexts, those three key concepts continued to rise to the surface: ritual, power and transformation.

Today, in the midst of the global Covid-19 pandemic, I see these three terms imbued with an entirely more powerful meaning. Surgical masks now speak of a complex and often contradictory system of symbolic value that will shift depending on their location: are you in a place where wearing a surgical mask is a sign of a particular political affiliation? Are you in a place where wearing a surgical mask is seen as a sign of weakness? Or are you in a place where wearing a surgical mask is seen as an act of socially-minded public health awareness? Is the surgical mask a sign of protection? Is it a sign of contagion? There is no one answer, because there is no single scenario that can be understood – even in purely symbolic terms – as being intelligible on a universal level. The real-world complexities of the stories that surround this new contextual landscape, in which the surgical mask now finds itself, is a nightmare of its own.

When I wrote the book, I knew that masks and face coverings more generally had a political potency stemming across history into our present moment – from the KKK to Pussy Riot, the appropriation of the V for Vendetta Guy Fawkes mask by Anonymous to the so-called ‘Burqa Bans’ that are currently in place in no less than fifteen countries around the world. But never did I dream when the book was published that the politics of the mask would become such a major component in how a lethal global pandemic would be conceived. In the light of this, the final words of my book ring truer to me now than they did when I first wrote them: ‘Masks are not in themselves inherently progressive or reactionary, but rather – and more significantly – we can now begin to value the diverse, varied and multiple ways that their meanings can shift and be adapted to suit certain contexts and support specific (and often competing) ideological positions.’ The final sentence feels even more urgent today, in the face of the real-world horror story of Covid-19 especially: ‘there is now and throughout history a fundamental politics about the human face and the power dynamics of occluding it, and horror film masks – through the intersection of transformation and ritual and power – play a long, fascinating and until now broadly unexplored role in continuing enduring traditions that speak to this precise power’.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas is an Australian film critic, speaker and consultant who specialises in horror, cult and exploitation cinema. She is a researcher at the Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne.